In interpreting Barry Goodman’s November 16, 2021 lecture entitled Ghost Writing: Phillip Roth, Franz Kafka, & Bruno Schulz - Living through Literature after Auschwitz, I trace how Phillip Roth connected his personal history and framing of self to Franz Kafka. Through this literary (re)imagination he inspired a revision of himself as well as inspiring and enabling a generation of writers following that literary tradition to this day.

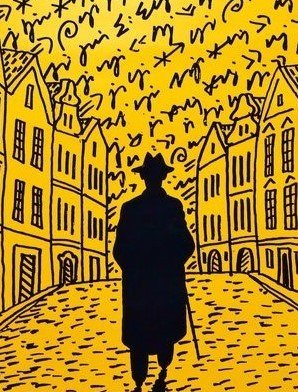

-the cover of Franz Kafka’s The Life and Work of a Prague Writer

Ghosts of Kafka

John Hill

Men with guns approach

Why? Here? What is his purpose?

A voice must be heard

So why was Phillip Roth in communist Prague in the year 1976? What were the circumstances under which he narrowly escaped detainment by the secret police following him, resulting in him not returning until 1989? And how was his mere presence in Prague symbolic in both understanding and shaping a particular niche of literary expression in the Cold War period? In his talk, “Ghost Writers, Living through literature after Auschwitz,” Barry Goldman gives us some answers, answers that connect to an emerging, underground literary expression that existed in and was shaped by the unique forces of Easter Bloc cold war tension and oppression in the 1970s. The story does not start with Roth, nor does it end with him, but Goldman uses Roth as a frame in which to view one person’s journey - both literally and figuratively. It was a journey that impacted Roth personally in his search for meaning as well as ultimately being a nexus that connected Franz Kafka and the height of Cold War persecution of Jews to a shared expression of post-Cold War geopolitics and resistance ghost writing.

Philip Roth, an Jewish-American writer who was emerging as a prominent writer in the late 1960s, made several trips to Czechoslovakia in the early 1970s. Roth’s travels in Czechoslovakia and other parts of the Easter Bloc had several purposes, and they were all tied together in a meaningful way. Roth was initially led to Prague to “find” Franz Kafka. Kafka, the Jewish German writer who had lived in Czechoslovakia, wrote in a highly symbolic and allegorical expressive form that inspired Roth. However, in being influenced by and replicating Kafka’s style, specifically with the release of The Breast (1972) along with the release of Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), Roth was met with visceral criticism from Jewish critics, foremost among them Irving Howe. Howe specifically referenced the “thin personal culture” displayed by Roth in his works, referencing Roth’s status as a 3rd generation Jewish immigrant living in free America, far different from Kafka and other Jews that experience the horrors of pre-Cold War persecution and current Cold War repression.

Roth, however, did seek authenticity in this understanding of himself and his heritage, and this desire to understand concomitant with his “search” for Kafka led to a journey of discovery and ultimately meaning that would be shared with the world. In traveling to Prague to retrace the steps of Kafka, he learned of a clan of banished, underground writers. This included befriending the intellectual critic Ivan Klima. Klima would be his guide on many of his travels. In retracing the steps and legacy of Kafka, Roth was also retracing his own steps and legacy, imagining places where his family had come of age. Furthermore, his “reality instructor” Klima showed Roth the harsh realities of the fate of banished intellectual writers in Prague, who had mundane jobs and were devalued. For an American Jew who was associating with and ultimately advocating for Czech writers laboring under the emergent repression of communist takeover of normalization, Roth himself became a target. The secret police had a special file on him labeled “The Tourist” (Turista) and were monitoring his every move.

In narrowly escaping Prague in the late mid 1970s, Roth would not return until the end of the Cold War. During this time Roth spearheaded and helped edit the Penguin Books paperback series “Writers from the Other Europe,” which featured many of the writers he had associated with in Czechoslovakia, including Milan Kundera, Polish writer Bruno Schulz, and Hungarian György Konrád. Many of the written works by these authors dealt with Holocaust-related themes, and they were turning to Kafka as a guide in their own “search” for him. The geopolitics of the Cold War led to a Kafka-esque type of subversive writing through what Goldman calls counter-realism, as expressed through counterfactual strategies of writing fiction as survival. It is this essence of counterfactualism that takes on the element of oblique symbolism and political allegory, reminiscent of Kafka. The Ghost Writer element of the work references the fact that the work is not a direct expression of the author, but the author being expressed through the characters and the trajectory of the narrative itself as a form of political allegory. This strategy allows the writer to constantly shift the expression of criticism to an innocent expression of the artifact itself or even to a sense of criticism of self rather than the state or “other.” The sense of self-criticism was key in sense making, accountability, and insulating the author from the accusations of direct criticisms of the state.

The Other Europe series became widely read and popular outside of Europe and popularized the works of Bruno Schulz, a contemporary of Kafka. Schulz’s works, including The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass were, according to Goldman, “more Kafka-esque than Kafka.” Schulz obscured his subject matter of cause and effect sequencing by going outside the linear, narrative tradition. With Schulz the organic becomes inorganic; the inorganic becomes organic. Time is not linear; nothing is final. Through the shared exposure and understanding of Schulz’s writing, one author (David Grossman) stated: “Schulz’s writing showed me the way to write about the Shoah and, in a sense, also a way to live after the Shoah.” The Shoah references the mass murder of Jews in Auschwitz. According to Grossman, Bruno’s (Schulz) Ghost was a major influence in the later generation of Jewish writers seeking a connection, meaning, and way of writing. Phillip Roth himself later wrote, “The only way to write about the Holocaust was as the guilty, as the complicit and implicated.”

As Goldman concludes his talk, he writes about how the writers that have emerged from “under Kafka’s cockroach” as he terms it (particularly Tadeusz Konwicki, Danilo Kis, and Milan Kundera) have, through the strategy and effect of counter realism, taken the writing criticism outside the binary of liberal, modern day socialist modes of writing or assumed dichotomous opposition of that writing, which is easily detected and subverted. As Goldman concludes, “Writing is inoculated by political allegory through fiction” and it also fashions a critique of self in a way that can be taken literally as an expression of guilt and desire of absolution. And to the extent that this strategy serves the dual purpose of avoiding submission, then we truly have Kafka meeting Bruno to create a modern, emergent ghost writer.

Roth’s literal journey to Prague was an attempt to understand - to understand Kafka; to find and connect to that which existed in Kafka and influenced him; to understand a part of himself and his Jewish legacy. But it was Roth’s figurative journey that led to the real discovery - a way to explore new “spaces” - spaces that harbored “safety” under the weight of persecution and repression; spaces carved out by others that he wanted to give voice to; the celebration of all that literary expression is and should be; and the ultimate sense that such expression can be turned inward toward accountability. The space of the self is at once the “safest” space to explore and the most resistant and difficult. Roth’s “journey” helped shape a particular form of literary expression that was inspired by the “ghost” of Franz Kafka. And to the extent that even Kafka fell under the geopolitical limitation of binary dichotomy, the introduction of Bruno Schulz added another “ghost”. The ghosts of today’s writers are still haunted by Auschwitz; however, in making sense of and taking accountability for Auschwitz certain “ghosts” do not haunt - they inspire and they guide.